In Cal Newport's Deep Work, a man named Adam Marlin spends every morning deciphering symbols on pages from the Talmud. The claim is that the sustained concentration exercises the brain, and the gained strength is useful for tasks unrelated to religion, like Adam's challenges as a businessman. To me, Knuth's book The Art of Computer Programming (TAOCP) also appears as a challenge of deciphering symbols and should serve as a Talmud for the gentile:

Should it be a rite of programming passage? Multiprecision integer division is just plain tough to get 100% right. And Knuth's description is hard to follow, with my small working memory able to keep only a subset of his single letter named variables in my mind at once.

The first hit on time will probably be that the current impplementation of bignumber will need to be augmented with a few new tools. You'll need the ability to access a section of digits at the most significant end of your big number. This could require a little time in the plumbing if you've abstracted the internal representation too far away from your typical means of access like I had. I'd also eliminated redundant leading zeros, but the dividend often needs to be padded on the left by one zero during the normalization phase.

On the Deamentia Mundo Blog I found that the Hacker's Delight book has implementations, one for 16-bit digits with native ops available 32 and one for 32-bit digits with native ops available in 64. Mirrors here and here. Warning: this implementation's "m" variable is the length of the dividend, but in Knuth's it's difference in digits between the dividend and divisor. So why write it yourself? If a coworker found out, you'd be charged with "reinventing the wheel". Well I think there is much value in reinventing the wheel sometimes. And there are so many wheels already invented that rule prohibiting one to never reinvent wheels would leave 99% of us completely paralyzed.

The algorithm is the gradeschool method. Knuth's modifications occur at three parts:

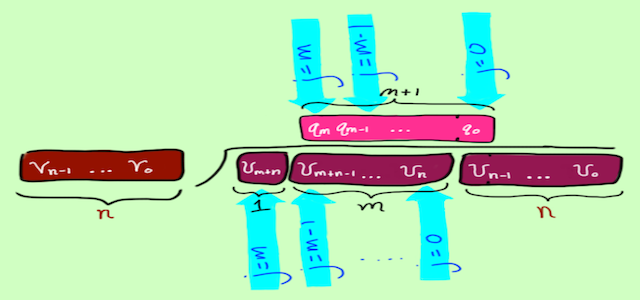

I'm nearly dependent on a mental picture, needing to imagine the loop variables moving across the data that they index, the data sizes in relative scale, and the result being built one digit at a time:

Here are some additional tips:

for(int i=0; i<N_TESTS_DIV; ++i) {

do {

generate_inputs(their_a, &our_a, true);

generate_inputs(their_b, &our_b, true);

}

while(bn_zerotest(&our_b));

mpz_tdiv_qr(their_quotient, their_remainder, their_a, their_b);

bn_div(&our_quotient, &our_remainder, &our_a, &our_b);

if(0 != compare(their_quotient, &our_quotient)) { /* ... */ }

if(0 != compare(their_remainder, &our_remainder)) { /* ... */ }

}

After I got it working, I discarded it. The first reason is that the Hacker's Delight (HD) implementation runs faster. Second, there are cases where the raw digit access used by HD's implementation is necessary, like during mulmod() and expmod(), where an array of digits has to temporarily hold a product twice as long as the bignums can hold. In other words, HD's implementation is more general. It can be pointed at any array of digits, whether it's within the guts of a bignum or alloca()'d or malloc()'d uint32_t's.